Why Did Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto Turn Right?

By: Nadeem F. Paracha

Even though the majority of amendments introduced in Pakistan’s constitution, and the intransigent ordinances that eventually turned the country into what is called an ‘illiberal democracy,’ were sanctioned in the 1980s during the reactionary Zia-ul-Haq dictatorship, many observers believe that the rot in this respect actually began during the elected regime of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto between December 1971 and July 1977.

Indeed, there is more than a hint of truth in this observation. But what really makes it interesting is the fact is that unlike Zia who had come to power through a military coup — claiming to turn Pakistan into a ‘bastion of Islam’ and a ‘true Islamic state’ — ZAB was an elected leader whose party had won the most seats in the former West Pakistan. And it had done so on the strength of a progressive, democratic and left-leaning manifesto.

Yet, it was during his regime that the national assembly okayed a constitutional amendment that not only ousted the controversial Ahmadiyya sect from the fold of Islam, but it is also seen as one which opened up a Pandora’s Box. This would (in the coming decades) unleash laws and ordnances that, in the name of faith, constitutionally enshrine religious and political prejudice.

So why did a progressive and left-leaning government allow the opening of this Pandora’s Box? Most commentators and historians who have in hindsight investigated the ZAB years, maintain that his regime started to move right from 1974 onwards. Of course, this could not have been a case of a popularly elected ‘leftist’ prime minister suddenly falling to the rightest side of the political divide on a whim. So what happened?

Firstly, it is important to at least briefly examine what leftist ideas such as socialism and liberal ideas such as democracy actually meant to ZAB and his party. Sometimes commentators have explained the mentioned shift in a rather hasty and myopic manner. They explain the PPP as a socialist-democratic party which (in the mid-1970s) suddenly turned right and became an authoritarian behemoth willing to exploit religious sentiments to stay in power.

Truth is there was nothing sudden, as such, about the shift. To begin with, the PPP when it was formed in the winter of 1967, was not a conventional socialist outfit. In a 1968 press conference Bhutto explained the PPP as a ‘broad-based platform of progressive forces.’ He said the inspiration of forming such a platform was Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s All India Muslim League (AIML).

A party is born: ZAB explained the PPP as a ‘board-based platform of progressive forces.’

In the early 1940s, Jinnah, to give the AIML a populist thrust and complexion, had agreed to expand it as a platform of varied elements who were on the same page as he was regarding the creation of a separate Muslim-majority country in the region.

So by 1944, along with the ‘Muslim Modernists’ in AIML, the party also opened its doors to socialists and even some Marxists. In 1945, the party added some ulema to its ranks as well.

Being a pragmatist, Jinnah saw the Muslim Modernists of AIML as being the ideologues who would continue to propagate a Muslim-majority country that was to evolve into becoming a progressive state without any hindrance from ‘Hindu majoritarianism,’ or, for that matter, from the ‘theocratic’ Islamic forces that had vehemently opposed the AIML as being a party of ‘nominal Muslims.’

From the socialists and the Marxists, Jinnah expected (to bring with them) the grassroots organizational skills of the party they were arriving from. That party was the Communist Party of India (CPI). The CPI had opposed the Indian National Congress (INC), dubbing it a ‘reactionary bourgeoisie outfit.’ It saw the AIML as a ‘revolutionary force’ and allowed some of its leading Muslim members to join Jinnah’s party. In fact, the manifesto with which the AIML contested the all-important 1946 federal and provincial elections in pre-Partition India, was authored by a member of the CPI, Danial Latifi.

In the ulema and pirs who had joined the AIML, Jinnah saw a way to answer his party’s critics on the right, especially those who were labeling him as a non-believer and his party as a ‘clandestine secular’ outfit. AIML also brought in many members from East Bengal’s Hindu community of the so-called ‘scheduled castes.’

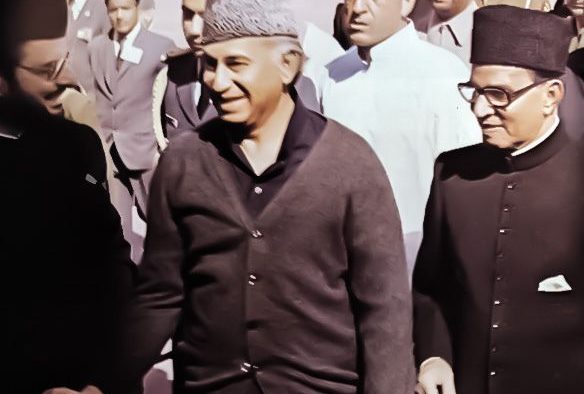

By the early 1940s Jinnah (second from left) had converted the All India Muslim League into a board-based grouping of Muslim Modernists, socialists, Marxists and some ulema and pirs.

Even though the PPP was the brainchild of a formidable Marxist theoretician, JA Rahim, and ZAB, the latter was first and foremost a robust pragmatist. According to a detailed study by Philip E. Jones on the top-down leadership and membership of the PPP between 1967 and 1970, the party had three main ideological camps within it.

The first camp was made up of seasoned socialist and Marxist ideologues and intellectuals. This camp also included some young leftist firebrands who had migrated from left-wing student groups.

The second camp consisted of intellectuals who had been working on an ideology which they described as ‘Islamic Socialism.’ Islamic Socialism as an idea that glued together socialist economics, liberal democracy and ‘the egalitarian aspects of the Quran’ was not unique to Pakistan. But what the intelligentsia in this camp of the PPP did was to adapt this fusion to local political, social and economic conditions and also borrow heavily from other strands of Islamic Socialism such as Arab Nationalism and Arab Socialism and Ba’ath Socialism (which, at the time, were all the rage in countries such as Egypt, Syria, Iraq and Algeria).

Work on Islamic Socialism in Pakistan had previously been conducted by Islamic scholars like Ghulam Ahmad Parvez and Khalifa Abdul Hakim. Much of their work in this context was also incorporated by the PPP’s Islamic Socialism camp. In the face of the criticism that the PPP received from some religious outfits who attacked the party of being ‘full of atheistic socialists,’ ZAB decided to explain the PPP as an ‘Islamic Socialist party.’ The slogan of the party thus became, ‘Islam is our faith, democracy is our polity, socialism is our economy. All power to the people!’

In its Foundation Papers (published soon after the party was launched) the PPP described its Islamic Socialism as a Pakistani (and/or Muslim) version of western social democracy which aims for a progressive and democratic welfare state and where the major industries are owned by the state to discourage ‘monopolistic and crony capitalism.’

The PPP was also vehemently anti-India and therefor largely nationalistic in orientation, upholding Jinnah’s Two Nation Theory. It imitated the idea of the Muslim Modernism of Pakistan’s founders to similarly suggest that Islam was a progressive and flexible religion able to adjust to current socio-economic realties and neutralize the need for a theocratic state.

Ironically, this was also professed by the Ayub dictatorship which the PPP opposed. The difference was that the PPP stood for parliamentary democracy, adequate provincial autonomy for the provinces and the promotion of folk cultures and the indigenous folk versions of Islam present in the region for over 500 years.

The third camp in the PPP mostly consisted of members of Sindh and Punjab’s landed elite that Bhutto explained as being progressive gentry who were ‘fully onboard with the party’s economic program.’ This camp was often at loggerheads with the socialist/Marxist camp most whose members came from urban middle and lower-middle class backgrounds. Also in the latter camp were trade and labour union leaders.

Bhutto also brought in some Islamic scholars into the party, most prominent being Kausar Niazi. Niazi had been a member of Abul Ala Maududi’s Jamat-i-Islami (JI). He broke away from that party to join the PPP after disagreeing with Maududi on matters like socialism and democracy.

On the surface it should have seemed that left-wing parties like the National Awami Party (NAP) would become a natural ally of the PPP. But there were fundamental differences between the two. NAP, which was formed in 1957, was an openly secular and socialist platform of radical Baloch, Sindhi, Pakhktun and Bengali nationalists. It considered itself to be a more mature leftist party compared to the PPP. According to Phillip E. Jones, shortly after ZAB was ousted by Ayub from the cabinet (for showing dissent) he had exhibited a desire to join the NAP but found that the party leadership was unwilling to accommodate him.

In 1968 NAP had broken into three factions. The one toeing a pro-Soviet line became NAP-Wali. This faction was the largest and was headed by Pakhtun and Baloch nationalists. The pro-China faction became NAP-Bhashani. This was led by the fiery Maoist Bengali nationalist, Maulana Bhashani. It boycotted the 1970 election. Then there was also a third faction. It was the Mazdoor Kisaan Party (MKP). This was made up of renegade Maoist NAP men who believed in an armed struggle to trigger peasant uprisings against the state. All these factions had vote banks in both the wings of the country, unlike the PPP that failed to construct a constituency for itself in East Pakistan. Also, unlike the PPP, NAP was not so aggressively anti-India. Nor did it give religion much space in its election manifesto.

NAP-Wali had strong electoral roots in Balochistan and NWFP.

When ZAB and the PPP came to power in December 1971 (or soon after East Pakistan broke away to become Bangladesh) it was a party that had been invited to rule a broken Pakistan. The invitation was made by a group of disgruntled military officers who forced General Yahya Khan to resign. The PPP had swept the 1970 election in the former West Pakistan’s two largest provinces, Punjab and Sindh. Being an ambitious man, ZAB accepted the offer.

Most of his biographers have described ZAB as being an egoist and a pragmatic politician. He was not an ideologue. In fact, he hated ideological rigidities. That’s why when in 1972 he ordered the police to crush a series of strikes by factory workers in Karachi, the very next year he threw out a prominent member of the party’s socialist wing, Miraj Muhammad Khan. Khan was the Minister of Labour at the time and had criticized Bhutto’s action against the factory workers as one that was against the PPP’s principles. ZAB disagreed, saying that the party’s economic program should not be made an excuse to create anarchy in an already struggling country. Miraj was arrested and thrown in jail.

ZAB comes to power.

In 1973 ZAB brought all the camps of the party in line to look for a middle-ground during the heated discussions with the opposition parties on the writing of the new constitution. If one goes through the contents of 1974’s National Assembly Debates Vol:1 and Vol:2 they can bear witness to how he managed to do this.

For example, he agreed to grant adequate provincial autonomy to the provinces to appease NAP which was part of the ruling coalitions in the provincial set-ups of Balochistan and NWFP (present-day Khyber Pakhtunkhwa). In the PPP’s discussions with the religious parties, ZAB agreed to rechristen Pakistan as an ‘Islamic Republic.’ The Islamic prefix first introduced in the 1956 constitution had been removed by the Ayub regime. He also agreed to make subjects like Islamiat compulsory at schools and colleges and introduce the teaching of Arabic. On the complaint of the religious parties, he asked his parliamentarians to remove the wordings, ‘Pakistan’s economy will be socialist’ from the constitutional draft.

Talking to the press he proudly claimed that PPP’s manifesto was not rigid and that it gave him a lot of space to be flexible. To him this was the truly democratic and progressive thing to do. Nevertheless, it should also be noted that during the same discussions on the constitution, the ZAB government completely discarded some other suggestions made by the religious parties in the assembly.

For example, PPP MNAs rejected the demand for making Islamic rituals mandatory. The party also discarded the demand for banning the sale, export and import of alcoholic beverages and the exhibition of ‘obscene content in film and on TV.’ The demand to close down liquor stores, bars and nightclubs too were discarded. The reason given was that even though the constitution will work against ‘all social evils,’ the bars and nightclubs were needed to continue attracting tourists who would bolster Pakistan’s economy and image, both of which had been badly battered during the 1971 civil war in former East Pakistan.

ZAB and his party members played a tense game of give and take with the opposition members in the parliament during the formative debates on the 1973 constitution.

By the time the 1973 constitution was officially passed and launched by the assembly, the PPP had clearly positioned itself as a social democratic entity but one which was also sensitive to the customs of the country’s Muslim majority. But Pakistan was one of the last major Muslim countries to adopt the Islamic Socialist ethos and experiment. It had already peaked and was on the vain in Egypt, Syria, Algeria and Iraq.

Then, due to the aftermath of the 1973 Arab-Israel War, oil-rich Arab monarchies dramatically increased petroleum prices. This act saw countries like Saudi Arabia and the UAE enjoy an unprecedented windfall of profits. The wealth greatly increased their influence. Following the example of Egyptian leader, Anwar Sadat, who broke Egypt away from the Soviet orbit and landed on the lap of the now incredibly wealthy Saudi Arabia, ZAB was quick to make a dash towards the sheikhs as well. In this he saw the potential of not only using the Saudis’ ‘petro-dollars’ to address Pakistan’s economic woes, but to also maneuver himself as the mind and political force behind the rising tide of Muslim power bankrolled by Arab money.

He won the bid to hold the second International Islamic Conference in Lahore in 1974. But before the conference was set to kick off, an incident in the Punjab city of Rabwah threatened to dislodge his plans to host a conference he had so meticulously planned. A brawl between some Ahmadiyya youth and members of JI’s student-wing at the Rabwah railway station triggered riots in the Punjab. As youth belonging to religious parties went about destroying Ahmadiyya property, the religious outfits and some Muslim League factions in the assembly demanded that the Ahmadiyya community be ousted from the fold of Islam.

The religious groups had tried this in 1953 but their movement at the time was brutally crushed by the military. At first, ZAB threatened to do the same and send in the military. But he hesitated and ordered the police to double its efforts to quash the violence. The violence, however, continued to spread from one Punjab city to another.

The religious parties demanded a debate on the issue in the national assembly. ZAB refused, saying the assembly was no place for religious debates. In his 1997 book, ZA Bhutto and Pakistan, Rafi Raza quotes a JI leader responding by reminding ZAB that ‘the constitution declared Pakistan to be an Islamic Republic. The parliament of an Islamic Republic had every right to discuss religious matters.’ Raza then informs that after being told that many of the PPP’s members in the Punjab Assembly were planning to take the opposition’s side in the matter, Bhutto finally allowed the debate to go ahead. The debate produced a bill which called for the 2nd Amended in the constitution: i.e. The ouster of the Ahmadiyya from mainstream Islam and the declaration of the community as a minority (non-Muslim) religion. The amendment was made.

Raza wrote that Bhutto was not happy at what had transpired. But being the egoist that he was, he basked in the accolades that poured in from the Urdu press and the opposition benches (sans NAP, which had kept intriguingly quiet throughout the episode). What’s more, he allowed his party to spin the episode as an achievement by claiming that the ‘PPP had solved the 90-year-old Ahmadiyya problem.’ ZAB then turned towards more pressing matters: The Islamic Conference.

ZAB is sworn in as PM after the passage of the 1973 Constitution. He had ruled the country as President between December 1971 and August 1973.

Almost all the heads of state and governments attended the spectacle, in which ZAB pleaded for the creation of a ‘Muslim Commonwealth’; a single Muslim currency; and the need to make the purposed Muslim Commonwealth as the ‘third superpower’ ‘to challenge the hegemony of capitalist America’ and communist Soviet Union.’

But the ZAB continued to find its original revolutionary rhetoric of Islamic Socialism incessantly at odds with new internal and external realities. After the country had lost its eastern wing, the religious parties had accused the armed forces of ‘indulging in wine and women’ and propagating a meek and even heretical idea of Islam. Bhutto on his part not only say that the officers had become decadent, but that they had also developed ‘Bonapartist tendencies’.

Whereas he had refused the 1973 demand by the religious parties to ban the production, sale and consumption of alcoholic beverages in Pakistan, in 1974 he decided to ban the serving of alcoholic drinks in the army mess halls. He also allowed one Major-General Zia-ul-Haq to lure the officers and soldiers towards daily Islamic rituals, hoping that this would erode the ‘Bonapartist tendencies’ that he believed had seeped into the mindset of the officers after Ayub’s 1958 coup. The Major-General had also begun gifting the officers books on Islam authored by Islamic scholar Abul Ala Maududi.

By 1976 the regime was competing with the religious parties to impress the wealthy Arab donors. But whereas the government was doing this by convening religious symposiums like 1976’s Seerat Conference, the religious parties were successfully tapping into the economic frustrations of the urban middle and lower-middle-classes and the industrialists who had been badly burnt by the regime’s half-baked ‘socialist policies.’

By 1976 ZAB was robustly competing with the religious parties to impress wealthy Arab donors.

Youth wings of religious outfits had become increasingly active on campuses in shaping a narrative which explained middle and lower-middle-class frustrations as a consequence of their spiritual alienation brought on by corrupted ideas of the Muslim faith (such as Muslim Modernism and Islamic Socialism) and forced upon them by a ‘decadent elite’.

The narrative went on to claim that an ‘Islamic revolution’ (which would produce a state and society driven by Sariah laws) was the only remedy. Then it posed the falling question: Was it not the full adherence to Sariah laws that had brought such ‘happiness’, wealth’ and ‘glory’ to countries like Saudi Arabia?’

Of course, the fact that Saudi Arabia and UAE were being ruled by autocratic monarchies and had been blessed by acres of rich oil fields was conveniently ignored, but the developing narrative did seem to strike a chord in the aforementioned classes.

No wonder then when the country’s leading religious parties joined some anti-Bhutto center-right parties to form an electoral alliance for the 1977 election, the alliance’s slogan was a demand for Nizam-e-Mustafa. By this the alliance (the Pakistan National Alliance [PNA]) meant an economic, political and social order driven by Sariah laws. Even though PNA’s manifesto was not quite so clear exactly how it planned to achieve this, the PPP retaliated by minimizing the word ‘socialism’ in its new manifesto. The manifesto again highlighted that ‘it was the PPP regime that had solved ‘the 90-year-old Ahmadiyya problem.’

The PPP swept the 1977 election. The opposition quite correctly cried foul and launched a violent protest movement in which dozens of people were killed. According to eminent historian and scholar, Khalid bin Sayeed, the majority of those who had poured out onto the streets on the call of the PNA belonged to the urban middle, lower-middle and trader classes. One is not quite sure exactly how they had perceived what such a Nizam-e-Mustafa really meant. But there is every likelihood that to many it meant a system like the one practiced in Saudi Arabia.

The PNA had encapsulated Maududi’s (albeit forcefully reasoned) Islamic Utopia into the slogan, Nizam-e-Mustafa. PNA leaders promised that such a system (nizam) would herald an economic and social revolution in Pakistan, eliminating crime, inequality, and immorality. But the PNA manifesto had said very little about what kind of laws would trigger and then govern such a nizam. This was because the three religious parties in PNA adhered to different interpretations of the Sharia.

Nevertheless, for the time being Bhutto was cornered and forced to sit with the opposition to thrash out a solution. He agreed to immediately impose some ‘Islamic laws’ demanded by the PNA. For example, in April 1977, he agreed to issue an ordinance banning the sale and consumption of liquor (by Muslims); and the closing down of all bars, liquor stores and nightclubs. Betting at horse racing too was banned. On PNA’s demand he replaced Sunday with the Muslim holy day Friday as the weekly holiday.

ZAB and his team on the negotiating table with the PNA men. He agreed to impose some ‘Islamic laws’ to appease the PNA men.

Nevertheless, on the night of July 5, 1977, his regime was toppled in a coup d’tat engineered by his own handpicked general. His name: Zia-ul-Haq.

To root out the ‘Bonapartist tendencies’ within the armed forces, Bhutto had encouraged the introduction of daily Islamic rituals in the barracks. He had also ignored the fact that Zia (as Major-General) was handing out books on Political Islam authored by Abul Ala Maududi to the officers and the soldiers. The military whose spiritual and political disposition till then had been largely associated with ideas such as Muslim Modernism was quick to grasp the fact that a more theocratic strand of Muslim nationalism which had been relegated and discouraged by the state, can now become the very idea with which a chastened military could reinvent and redeem itself into becoming an influential state entity once again. Zia had closely observed how the slogan Nizam-e-Mustafa had galvanized many Pakistanis against a powerful PM.

In April 1979, ZAB was hanged through a sham trial. Ironically, the religious tide he thought he had managed to surf well before the religious parties, pulled him under and ended his life. The rest, as they say is, Zia.

Naya Daur Media (NDM) is a bi-lingual progressive digital media platform aiming to inform and educate Pakistanis at home and abroad. Subscribe to our YouTube channel here Follow us on Facebook Twitter and Instagram

Fact based article. I think after the fall of Dacca country was also in search of new identity, Islam can provide it that very umbrella. It can help you against India, strengthing your ties with emerging middle class. For the time being it can appease Islamic political parties and Muslim population. Bhutto might have think he will be able to mange this monster, but he underestimate it, and rest is history.

A gross injustice to the legacy of ZAB, the author feigns liberalism without understanding its meaning. ZAB is rightly credited with infusing a feudal peasantry with their right as the working class and giving the nation a democratic constitution. The spirit of theocratic governance was infused in the nation based on the methodology of its creation by secular forces, when you have this onslaught of history, tradition and imperial forces manipulating those, you have to maneuver, drop ideology and clutch at straws to remain afloat to fight another day. ZAB gave us a solid foundation fighting the powers that be including imperial powers.